Category: Blog

-

The Health Effects of Leaving Religion

“a person’s faith, or lack thereof, is often so important that it affects physical, as well as spiritual, well-being.” https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/the-health-effects-of-leaving-religion/379651/

-

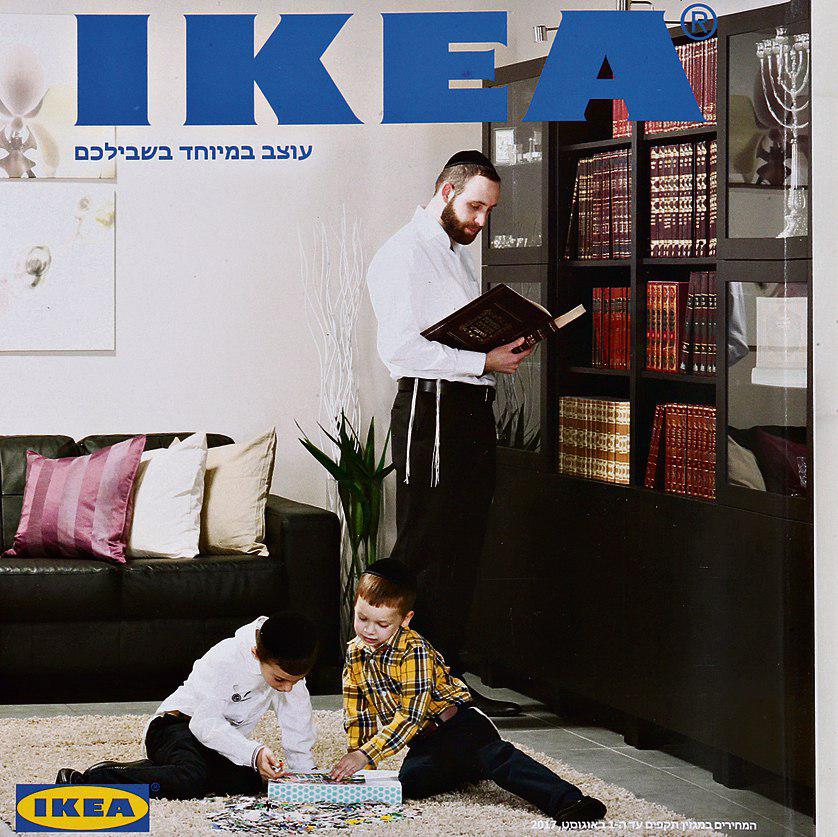

Second Generation Israeli OTDs

http://www.jpost.com/Magazine/THIS-NORMAL-LIFEDatlash-20-the-elephant-in-the-room-532865

-

Sh*t People Say to OTD People

Excellent article from imamother.com: http://www.imamother.com/forum/viewtopic.php?p=2777212